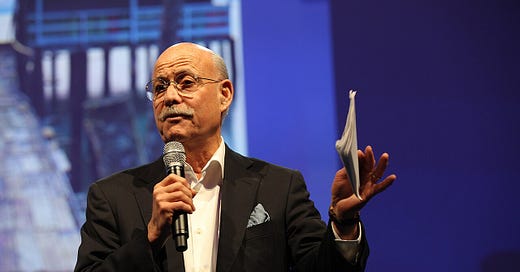

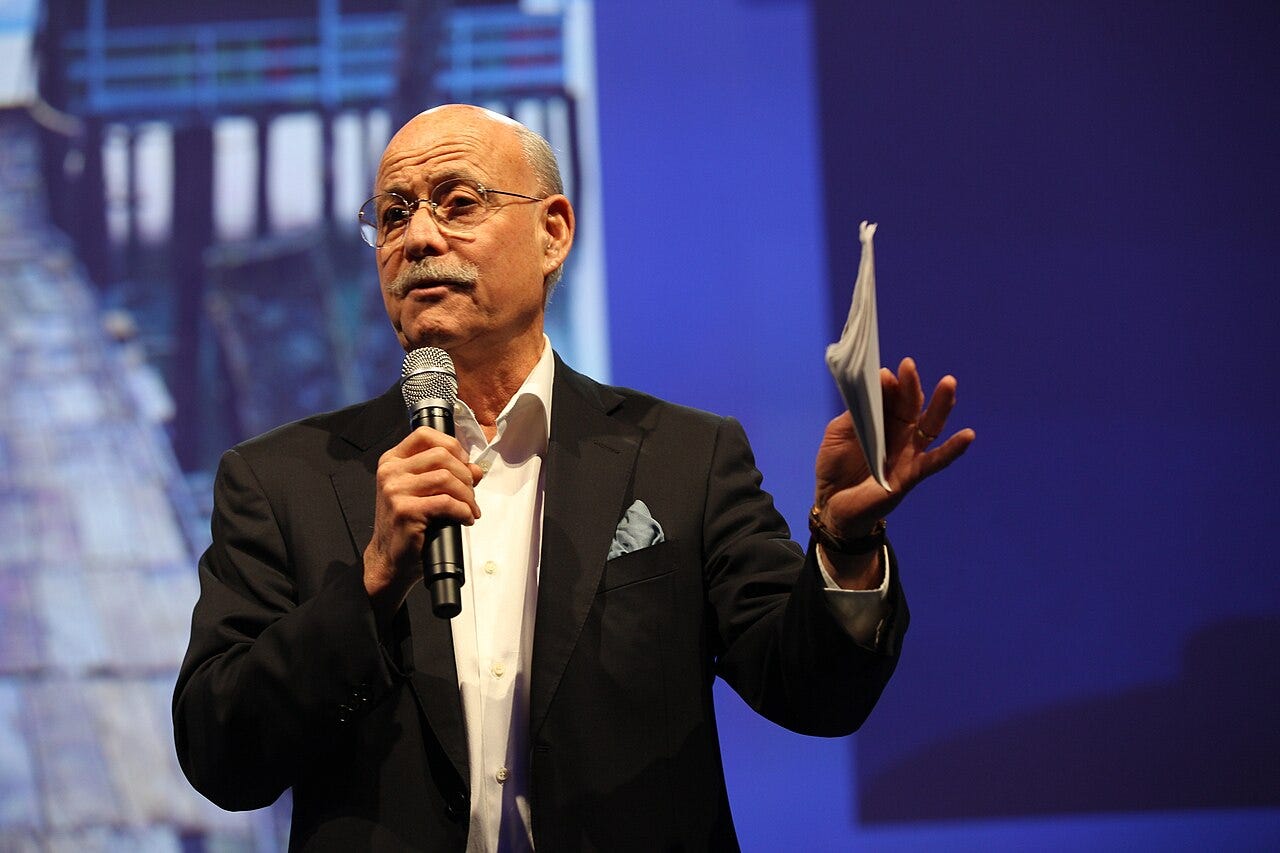

Infrastructural Revolutions and the Age of Resilience: A Conversation with Jeremy Rifkin

Interview by Anders Dunker

The American economist Jeremy Rifkin has had a major influence on the theory and practice of the green energy transition, both as the author of numerous books on technological changes and as an advisor to China, the European Union and the Biden administration. Rifkin is perhaps best known for his futurist predictions, famously analysing digitalization and the labour market in The End of Work (1995) and predicting smart networks of renewables in The Third Industrial Revolution (2011). He has authored specific critiques on topics such as genetic engineering and beef production, as well as numerous critical books on cultural history and the future of civilization, such as Entropy (1980), Time Wars (1987) and The Empathic Civilization (2010).

In his latest book, The Age of Resilience – Reimagining Existence on a Rewilding Earth (2022), he unites these two tendencies to formulate a new, and in many ways, original review of environmental and economic thought. Drawing on natural science, original historical analyses, and political theory, he presents a profound critique of modernity, but nevertheless retains a strong belief in technological solutions and moral progress carried forward by new generations. Anders Dunker, Technophany’s commentary correspondent, interviewed Rifkin in a long conversation over Zoom. This interview is also complementary to Technophany’s Special Issue, Entropies.

Anders Dunker: At the beginning of the 1989-editon of your book on thermodynamics and culture, Entropy – Into the Greenhouse World, you describe the year 2035 with runaway wildfires, floods in New York leading to attempts to build a dam around Manhattan, and the mighty Mississippi River drying up so much that it has to be closed to boat traffic. All of this has come to pass in recent years. The Earth seems to be changing even faster than your predictions?

Jeremy Rifkin: Yes, these things are already happening. When I made these claims, everyone thought I was crazy, but it really wasn’t rocket science. Actually, anyone holding their ears open could tell which way we were going. The first version of the book, Entropy, A New World View, which came out in 1980, was the first book published after the National Academy of Sciences issued its first climate report.

Now the situation is different, and people are watching these events play out in their own communities. The blizzards are rampant. The spring floods last for months. Then come the summer droughts, heat waves and wildfires, and then the hurricanes. People see that this is the “new abnormality,” as former California Governor Jerry Brown has said.

I think what we’re seeing now is that the age of progress is on its deathbed. The reason no one talks about it, and no one is able to grasp it (including the international institutions, think tanks, UN Climate Conference), is that it is precisely the assumptions, narratives, worldviews, ways of life, and political practices of the age of progress that have brought us to the brink of extinction. Fossil fuels just happen to be the centrepiece because they are fundamentally about how we understand the state, the economy, nature, and science, how we raise our children, and how we value ourselves. It is about the way we conceive of government, our understanding of the economy, our relationship to nature, how we approach scientific methodology, how we educate our kids, and even how we consider self-worth and what it’s all about. And so that’s the big unspoken. It’s not as if anyone is unwilling to articulate it. They’re not hiding it. They just don’t know. It’s the way we live in all those dimensions—and the culmination of the age of progress—that’s taken us there.

AD: In your latest book The Age of Resilience, you present a critique of efficiency, as a fundamental value and ideology in the age of progress. What is at stake in this critique?

JR: Everyone thinks that efficiency, which is the time value we operate with today, has always been here and is something universal, but there is no efficiency in nature. If we look at the history of hominids—we’ve been here for millions of years—our approach to time in most of this period has been adaptation, not efficiency.

For every species on this planet, including ours, the original temporal orientation is adaptivity, not efficiency. And that adaptivity is found in our internal biological clocks, which are in every cell’s orientation. But the biological clocks in every cell, organ, and tissue are temporally adapting to the rotation of the earth every 24 hours. That’s the circadian reference. They’re also temporally adapting in every cell and organ to the tidal changes on the lunar cycle. Every moment of every day they’re adapting to all those changes going on in the other spheres as they relate to the rotation of our Earth and our travel around the sun.

The big change came about 11,000 years ago when the last Ice Age receded at the end of the Pleistocene. At the beginning of the Holocene there was a good climate, and, in this period, some groups of foragers and hunters became sedentary, and others followed suit. We got agriculture, pastoralization, then the big hydraulic civilizations, all the way to the proto-industrial, and then the industrial age, the age of progress. We began making nature adapt to us rather than us temporally adapting to nature. That’s the big reset in history.

The late Renaissance thinker Francis Bacon said, “Man was not created for the earth. The earth was made for man.” We had to distance ourselves from nature and observe it and use inductive and deductive thinking to steal knowledge from nature so that we could adapt it to us. This led to the age of progress and the depletion of the earth. But nature is not efficient. In nature, there is no growth. There’s flourishing and thriving.

AD: You started exploring the ideologies of time and efficiency in your 1987 book, with the polemical title Time Wars – The Primary Conflict in Human History. What does it mean that efficiency is not only a measure, but what you call a time-value?

JR: Efficiency builds on a radically new understanding of time, which really emerged during the late Medieval period through to the Enlightenment. The Benedictine monks wanted a mechanical clock so they could do their canonical hours, but they certainly did not intend for all this to happen. But then the urban communes took over the mechanical clock. It was the beginning of industrial factory work in the textile industry. And then came the agreed-upon time zones around the world, global synchronization, it all emerges. New infrastructures change our temporal and spatial orientation. They annihilate time and space in various ways. They change the way we perceive the passage of time and our orientation in space. And the weird part of all this is that everyone thinks efficiency, which is our time-value today, has been here forever, but it is really something new.

AD: What you call efficiency as a “time-value” seems to have become really explicit with Taylorism and mass production, but already Adam Smith writes about it in The Wealth of Nations (1776), where he points out that it would take an artisan an hour to make a good needle, while a needle factory could make thousands and thousands a day. Doesn’t efficient production also mean that you avoid wasting resources, including time. Can’t efficiency, then, be a good thing, an optimization, even from an environmental point of view?

JR: I have to stop you, because right here lies the problem! You don’t waste resources: that’s just the come-on line. What happens is that you optimize with the least amount of resources used. But if you optimize, you’re also using up resources quicker and quicker. Which is why efficiency is the premiere temporal orientation that’s taken us through the age of progress into extinction. And that involves extracting ever larger volumes of the four critical spheres. The hydrosphere, the waters, the lithosphere, the soil and of the trees, plants, the animals, the atmosphere, the oxygen, with the biosphere encompassing them. Extracting more volume at greater speeds and shorter time units. Then we wonder why we depleted the planet, depleted the soil, toxified the ocean—that’s it! Nature doesn’t work that way.

The twin for efficiency is productivity, your inputs, and your outputs. Producers want to optimize the output and not minimize too much the input, so they can return investment to the shareholders. But what they don’t price is all the externalities that happen at every single time you make a shift in what you’re doing with that good or service.

So, what they’re not counting in economics is how the externalities ripple out every single time there’s a transformation in that good or service on the way to you and me; there are externalities rippling out across the entire planet and they overwhelm whatever little added value you have at that moment in the production of the supply chain. It’s called the toxification of the ocean, the pollution of the soil, the elimination of the forest, the poisoning of the atmosphere.

AD: There’s a lot of talk about externalities, but it seems to be a huge practical problem to factor them into the economy in a systematic way. We are thus haunted by a discrepancy between the economy and the environment. Taking off from Marx, Bellamy Foster, from out of Capital, has developed his theory of a “metabolic rift,” describing how the flow of resources in our social systems violates the processes and cycles of nature.

JR: There remains a discrepancy between the economy and the environment. The problem is that Marx had more or less the same understanding of time, space, and productivity. He only wanted the workers to get the lion’s share of the profits instead of the capitalists. Engels wrote a book on the dialectics of nature that was not so bad.

I taught management at the Wharton Advanced Management Program for fifteen years. Back then, every other sentence was about efficiency. Today, I no longer hear that word in this business environment I once belonged to. They are now talking about adaptation and resilience. But they don’t realize what it really is. They think it’s just about making more solid buildings or business structures. But to make your economy align with ecology, you would need a whole new worldview based on the laws of thermodynamics.

AD: You’ve written extensively about society and the second law of thermodynamics. Entropy is, among other things, about a gradual loss of available energy, and hence about irreversible processes of consumption. The Romanian economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen pointed out, before most other analysts, that the economy is unable to account for what he calls “non-renewable resources,” which has become a major issue in our time.

JR: Entropy is about the loss of disposable energy, and hence about irreversible processes of consumption as well as a kind of overheating. Georgescu Roegen pointed out—among other things—that economy failed to count in what he called “depletable resources,” which has become a big topic in our time.

Georgescu made a really good point in the afterword of my book on entropy, and he talked about material too, that there are three types of systems in the world: open systems that exchange matter and energy, closed systems that exchange energy but not matter, and isolated systems that don’t exchange either. We are closed. We exchange a lot of energy with the rest of the world, but not a lot of matter. Matter is a form of energy that’s still frozen; and because it is energy, it too is subject to the second law of thermodynamics and becomes more dispersed and no longer usable, et cetera. Rare raw materials, the so-called rare-earth elements are becoming more dispersed, fragmented and less available. When you use up the coal, oil, and gas, which are the burial grounds of the carboniferous era from 350 million years ago, that’s not going to come back.

The basic idea of Newtonian mechanics is that all changes can be reversed. With the second law of thermodynamics, all of those changes. Many prominent scientists have tried to tell economists this. But the economy clings to theories based on equilibrium. They don’t factor in time, and time means energy changes.

The economy is a moribund discipline, Georgescu-Roegen warned them. If we understand how the planet works, we realize that we are operating quite the opposite of what it takes to maintain a commons that actually allows life to flourish. Nature is diversity and redundancy. Efficiency, on the other hand, means eliminating all friction. If you have too much in stock, then you have expenses and may not provide enough dividends to investors. That’s why you get rid of the stock. You also don’t want too many workers, just enough. Then came COVID-19: Where are the ventilators? Where are the masks? I have no more toilet paper! Less diversity and less abundance mean more monoculture and greater risk of collapse.

It was Condorcet, the French aristocrat who, while they were trying to guillotine him wrote that little essay, “Progress of the Human Mind (1793)”, and here I paraphrase, “There is no impediment to the perfection of humanity, and progress has no other limit than the duration of the globe.” Faith in progress is rightly failing, and this new sentiment became apparent when Emmanuel Macron delivered his speech to the French nation in September 2022, in which he declared that “the age of abundance is over” and that “the time of sobriety is here,” meaning the age of progress is over. The age of progress, as mentioned, was in its time the culmination of our adaptation of nature to our utilitarian needs. In business, you hardly hear of progress anymore, except for the Metaverse people and the Silicon Valley singularity gang.

AD: Nonetheless, the ancien régime of fossil fuels still holds up. The French Revolution rose up violently against the aristocracy, based on the premise that no one voluntarily relinquishes power. You seem to understand technological revolutions as more trustworthy engines of change than political revolutions—building something better, rather than opposing the old, to paraphrase Buckminster-Fuller…

JR: My own anthropological and historical writing is based on the notion that the big economic paradigm shifts have been few and far between and that each one of them is a transformation of infrastructure. And there’s been about seven or eight that you could qualify as that, because they’re fairly serendipitous.

I describe this in The Third Industrial Revolution (2011), how certain crucial technologies crystallize in society and create a new infrastructure. What historians and economists do not understand is that infrastructure is not a product of the state, rather it is the state that is a product of infrastructures. Infrastructures determine the actual scope of opportunity in which the economic models can develop. The same applies to the state: new forms of state are emerging as a result of the technological revolutions of infrastructure. There are many forms, but they cannot go beyond the possibilities and limitations that infrastructure dictates. For the economy and society, the same applies.

And let me explain what I mean by that: Like every infrastructure, the first and second industrial revolution infrastructures tell you what kind of economy governments can have. So, they were vertically integrated to trade economies of scale. No monarchy, no rich family could afford to put in a telegraph system in the last half of the 19th century in Britain or in America. It was simply too expensive. Nor could they afford to put in railroads for transport across our continental frontier of Britain. Nor could they afford to move easily from deforesting for energy to coal and having that distributed throughout society or creating dense urban environments for your railroads.

When the first industrial revolution hit in Britain, there was plenty of steam power. They shifted their power source to coal and steam engines on rails, and created dense urban environments, national markets, nation-state governance.

Then came the second industrial revolution, centered in the US, with the telephone, which Graham Bell really moved out quick, then radio and television followed. Cheap Texan oil replaced much of the coal. And then our Henry Ford stole the Daimler engine and he put out a cheap car, which revolutionized transport. It went from urban to suburban, national to global markets and globalization, global media institutions. Eventually, a handful of companies took the lead in the fossil fuel age, and much of this vertical integration kept happening even in the third industrial revolution. And now we have 500 dominant global companies that are all vertically integrated, and in every industry only a handful control the market. These 500 account for a third of world GDP. How many employees do they have? 65 million people out of a global workforce of three and a half billion. And the eight richest people in the world have a combined wealth equal to the wealth of half the people on the planet. Eight people.

AD: In a way, it becomes a question of who owns the Earth?

JR: Which is why I talk so much about the commons in The Age of Resilience. The land should not be made property at all. The lithosphere, where the oil and minerals are located, is a commons, the atmosphere is a commons, the hydrosphere is a commons. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t adapt and use parts of these for our needs. But Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to win the “Nobel Prize in Economics,” hit the nail on the head. She showed that throughout history, the commons have been present long before capitalism—and they are still here in the form of cooperatives, which to this day comprise about 1.5 billion people and one in ten workers. They are not mentioned in a single sentence in business schools.

But until our time, many commons and small communities all over the world were careful not to take more out more of the ecosystems than they could renew themselves. They knew they had to do it that way for the sake of future generations. In the Alps, there are still commons governed by thousand-year-old communities, and they function. So, there are other ways of doing things. Collaboration is not a zero-sum game, but one adapts to what nature can provide. One limits the population, consumption. It becomes part of the culture. Not all pre-industrial cultures managed it. The hydraulic civilizations did not do so well, for they created erosion and degraded the soil.

AD: I take it that what you—with Lewis Mumford—call hydrological civilizations were the first ones to attempt to control nature on a large scale, in order to make production more efficient and predictable?

JR: The waters move everything else. Vladimir Vernadsky, who came up with the idea of the biosphere, has got a whole history of the waters. And in modern times, Lynn Margulis, who actually was more important than her partner [James Lovelock] in developing the Gaia theory. I suppose what we’re not coming to grips with is how the hydrological cycle is the prime movement.

Water goes against the mountains and weatherizes the mountains, so they decay into sediment, and all the elements in those rocks then become part of the soil. They are the soil, the base. Then the soil with those elements goes to the plants, the animals, and then into our body. This phosphorus in my tooth, this came from mountains and it’s going back there after it’s on my tooth. The hydraulic civilizations born in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley of India, the Yellow River in China are important because their crucial premise is: without water, no life.

AD: The early civilizations manipulated the flow of water, sometimes with detrimental results and some pyrrhic victories over nature. Today we manipulate or inadvertently affect almost every material flow on the planet. Can an industrial civilization successfully inhabit the planet through a future conceived on the scale of deep time? Can a large-scale technological society be made sustainable at all?

JR: I don’t think we’re that far from getting there. As I mentioned earlier, new infrastructure creates new forms of government and economic systems. And it changes the way we communicate, power, and move our social life or economic life and governance: communication revolutions are converging with new energy revolutions that converge with new mobility. Logistics can bring larger numbers of people together with more differentiated skills into a social organism to maintain society. Infrastructures are a social organism. Every cell in every body and every species has to have some means to communicate, a source of energy and some mobility. Infrastructures change our perception of the passage of time and how we orient ourselves in space. In this sense, they negate space and time in various ways.

Now we have four and a half billion people on the internet, and with our smartphone we hold a technology in our hand that is much more powerful than the one used to control the moon landing. The communication internet is already being connected to the electricity grid. We now have millions of people producing their own solar and wind power. The power they do not use, they send into increasingly developed regional “energy internets.” In ten years, they will span continents, in twenty years they will stretch over land and ocean via cables and become global. So, when there’s sun in one time zone and you need the electricity in the other, it can be sent through. You can also store it. Or, when there’s wind in one part of the world, when the planet’s rotating, send it to the place where there’s sun. This is a whole new way. And it forces us to move from geopolitics to a kind of biopolitics.

AD: Such a development requires a high degree of international cooperation, which after the Russian invasion of Ukraine doesn’t exactly appear easier?

JR: That is true for now, but in the future, with such an energy constellation put in place, you simply won’t need a big military, because sun and wind is found everywhere. And no country will ever be able to control every landscape on Earth, that’s not possible. In fact, the transition from defence to resilience is already underway. Who responds when natural disasters occur in the United States? National Guard and federal forces. They haven’t realized it yet, but they've gone from defence to resilience—in the US, they are the ones who to deal with the climate disaster. With wildfires, droughts, floods. It’s terrible. They just haven’t recognized it yet, but that’s what they’re doing, resilience defence.

We have already talked about the First and the Second industrial revolution. I mentioned the third industrial revolution on page one of The End of Work in 1995. We all saw it coming, the Nobel Laureate Wassily Leontief who wrote a piece for the book and Robert L. Heilbroner who wrote the introduction. I was just chronicling what we were doing to some extent. But what we realized from the beginning of computers in the ’50s to commercialized computers all the way to then, something was going on. At the time when I declared, “This is a third industrial revolution,” it was already being put into practice. And we began to see a new infrastructure, a new communication revolution, the Internet. Now four and a half billion people are on the Internet; their smartphone is a more power computer than sent our guys to the moon. In one little palm of your hand, amazing. Talk about power being distributed.

I think that what we’re seeing now, is the beginnings of a shift that we did not see in 1995 as we move into this third industrial revolution infrastructure of the three Internets (communication, energy, and things). What we began to notice in Europe when we worked there with each of the four presidents of the EU and the European commissions (and we worked with China on their 13th and 14th 5-year plan)—and we didn’t see any of this as it emerged—is the rise of a digitized infrastructure of communication, energy, mobility and logistics.

It has started to morph into something that isn’t just an industrial infrastructure, although it is just the beginning. By the late 2040s—if we still are able to go on—this will be the first of the resilient infrastructure revolutions.

I think what we’re seeing now is the beginning of a shift that we couldn’t see in 1995, when the Internet came along: “the communication internet” connects to the “energy internet”, which in turn connects to the Internet of Things and automated transport and logistics. Something interesting happens in the energy transition, because solar and wind power force us to share networks. There is no way around it. Because when it is sunny in one part of the world, you have to transport it to another where it is night. And when there is wind in one part of the world, you have to send that energy to where there is no sun or wind. In this way, we are also forced to think planetarily.

What we also see is that we are in the process of establishing a digital nervous system for the planet, where the satellite systems function as the brain: Galileo, GPS, and ATON satellites. In addition, we have sensors placed around the world, which connect the brain to the nervous system. We have sensors in nature that help us monitor climate change and ecosystems. We have precision agriculture, precision manufacturing, smart homes, smart means of transportation. The planet will be connected in a digitized brain and a digital nervous system.

AD: James Lovelock, the originator of the Gaia theory wrote about this in his latest book before he died, the Novacene. He was very, very optimistic when it came to this planetary nervous system. On the other hand: Peter Dauvergne wrote a book called AI in the Wild, and a recent book by Benedetta Brevini simply called Is AI Good for the Planet? Both books focus on the argument that AI is just going to exacerbate all the bad effects of global capitalism. It’s just going to make exploitation and extraction more effective.

JR: Well, they have a good point. On the other hand, it is not necessarily about adapting the earth to ourselves, but to adapt ourselves to nature. That is why we need the infrastructure of the third industrial revolution: it’s a planetary monitoring system. And for water internets, energy internets, you need to have it. You won’t be able to control the sun and the wind. If water moves energy, energy moves water. If the electricity grid goes down, the water stops for 72 hours, with no water you’re in trouble. So, I have no problem with using the virtual infrastructure for infrastructure alone. The amount of data is now becoming so enormous that you can’t integrate the systems vertically anymore. If an electric vehicle is about to crash, send that data back through the cloud to a remote data centre. So, they’re now introducing fog computing, not cloud computing. We’re going to get billions upon billions of edge data centres that can be fluid and agile and come and go. And they favour small and medium sized enterprises in cooperatives, blockchains or platforms, so they’re also fluid and agile. So, as the climate changes really radically moment to moment, do you think those big vertically integrated organizations are really going to be able to handle this?

And one of the things we’ve been doing recently is that our companies and industries have been conducting these infrastructure deployments that trace the changes that we didn’t see at first; changes that now we see keep turning up. And as we see these changes brought out by this infrastructure, we’re beginning to see what its maturation point will be: the third industrial revolution. By the late 2040s, I’d say, you’ll have the resilient infrastructure in place. As the inventor of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners Lee said that everybody at the margins will deal directly with each other, that we don’t need some big vertically integrated operations centre to be the referee. But, counter to this idea of internet, then Microsoft came around and Google and Facebook and Dell, and they vertically integrate, all of them. They won’t be here, I think, in 30 or 40 years from now.

AD: Really? How so?

JR: Some of them will stay, but they’ll be aggregators. The new resilient infrastructure favours small and medium sized enterprises in cooperatives, blockchain or platforms, so they’re fluid and agile. But you’ll have ecosystems of technologies, involving much more redundancy and diversity. You’ll have rich infrastructure ecosystems that are part of natural systems—resilient infrastructures. You can either withstand or you can adjust to the changes that the climate brings. Try to imagine these big giants doing that, they couldn’t even handle the pandemic.

So, we can use the digital infrastructure to monitor and respond and adapt. But the data is always past data. So, you’re trying to make future predictions on past data. Well, nature is so unpredictable. It’s so complex that the best we can do is not try to pre-empt it. We’ll never do that because the feedback loops are well beyond any past data to tell us what’s going to happen.

AD: So, alongside the automated systems, we have to think and plan together, even if our situation is unpredictable. You’re talking about an earth as “rewilding,” not in the form of projects for restoring wild nature, but rather as something nature does on its own accord?

JR: For example, climate change is in a sense “rewilding” the water cycle. According to the laws of thermodynamics, for every degree Celsius the temperature goes up, the atmosphere can absorb 7 percent more moisture. More heat creates new weather systems, and moisture is driven faster from the soil up to the clouds, so you get torrential rainfall. Record snowfall and rain alternate with drought and wildfires. They affect ecosystems and cross all national borders. Therefore, the activities of the authorities must be expanded: we can still have nation-states, but we must think politically in terms of bioregional authorities.

AD: Which brings us back to the commons?

JR: Here, the United States is ahead of everyone else. The Cascadia bioregion has become quite famous: two US states (Washington and Oregon) and one province in Canada (British Columbia). There is also the Great Lakes: eight U.S. states (Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York) and one province of Canada (Ontario). Twenty percent of the world’s fresh water is found here. There, they have developed a common legal framework over thirty years. Europe has done nothing close to this. China has been next to take up bioregional rule. In September 2022, the Chinese government announced that it would create eight bioregions. Such regions create many new jobs in ecosystem management and ecosystem services.

These countries take ecosystem protection seriously because their economies depend on it. They try to adapt to nature, rather than adapt nature to themselves. It’s a big shift.

AD: And a crucial part of the transition to a resilient civilization, as you suggest? We may have thousands of years of severe climate systems and imbalances ahead of us.

JR: The Smithsonian Museum of National History published a fascinating article that posed the question of how the early hominids could survive in an extremely unstable climate with unpredictable habitats. They have found that our ancestors have lived through incredible temperature fluctuations, with ice ages lasting 100,000 years, followed by 10,000 years of warmer temperature, followed by new ice ages. How did these relatively fragile ancestors and foremothers of ours survive? The answer lies in adaptability and flexibility, and it hinges on a big brain and social instincts. What allowed us to participate in and learn from the lives of other species? The beaver is building a dam. Well, we can also build dams. The bird builds a nest. We can also build nests. And language helped us pass this knowledge on to new generations.

AD: Yet it was the same ingenuity that later evolved into a technical mastery of nature and the decimation of many of these same animals. The Anthropocene is an age of extinction, disruption, and supreme danger, which is why Bernard Stiegler, the French philosopher of technology, emphasized that it is an epoch that we must by any means surpass—not identify with or settle into. In his last years, he was concerned with the idea of epochs and the lack of epochs, which to him both meant an absence of epokhé, a philosophical and critical distance which makes it possible to change one’s gaze and one’s way of thinking—and an absence of a shared vision, a projection, or a project.

Among your more daring suggestions is your book-length proposal or prophecy of a global age of empathy; this gives some cause for optimism.

JR: The industrial age didn’t get a term until the economic historian Arnold Toynbee—the uncle of the famous universal historian by the same name—did some lectures in the 1880s, well after the industrial age was there. Because people didn’t see it. I should say that we, our global group—including a lot of companies, architects, and urban planners—we didn't see back in 1995 how communication, energy, mobility, logistics would start to metamorphize into what I described earlier. The resilient infrastructure is very different and more ecologically oriented. I had to see it before it emerged for me, and I think once it emerged, we could name it. It’s moving from a third industrial revolution to the age of resilience. And my interest lies in this third industrial revolution.

The thing about optimism is that it doesn’t do any good for an activist to be an optimist or a pessimist. It’s a total waste of time. Optimist: wait for the good news. Pessimist: wait for the bad news, which is often self-affirming. I’m guardedly hopeful, but I’m not naive. So that’s where activism comes in. Millions of young people have gone on school strikes for the environment in 143 countries. We humans love to protest and have done so for thousands of years, but this time it’s different. After talking to some of these young people in Milan, I understood what makes the protest special. This is the first protest in history in which an entire generation around the world sees itself as one species, as an endangered species, and the other species as branches of the same family.

Empathy is crucial, since it makes it possible to experience the distress of others, to feel what others actually physically are feeling. Hunter-gatherers had this to the highest degree. They had to kill animals, but they asked for forgiveness while it happened. And it’s not just some New Age idea: they actually did it. So, there’s a source of hope here, but the problem with empathy is that it can disappear at any moment.

The new sense of community is a major change, and it will affect all the other forms of consciousness that will continue to fight historical battles that are still there, marked by tribes, groups, religions, and ideologies.

AD: What about oligarchy and hegemonies, raw and entrenched power that no one will give up voluntarily or out of moral pressure?

JR: The new identity as a species, the new community with other species, is seen as a threat. The other forms of consciousness have not disappeared. As we speak, religious and ideological wars are taking place in which group identities are at stake. And when they see an identity that is broader than their own, we get a backlash. But it might be different this time, because now survival is at stake. And you can still have your ideological ties, religious ties, blood ties, and so on, why not? But only as long as we also see ourselves as a species, and as an ecosystem that is part of the planet’s ecosystem. Either we make this turn in our way of thinking and acting, or we don’t.

Young people must go beyond peaceful demonstrations. I see it as a struggle and the young people have to show that they hold their ground. They need to get involved in politics. If not now, when? When these young people are my age, 79, I can’t imagine what the world will look like. If we only manage to keep the global temperature below two degrees, that would be huge.

And one has to take part in it in whatever way one can. Also, one doesn’t have to be some intellectual giant. I was an average student in a public school in the south side of Chicago. And my teacher said, basically, given his talents, he’s doing fairly good compared to the other kids. But I wasn’t doing that great. Anybody can do what you and I are doing. Anybody. It’s a matter of desire. It’s a matter of how one perceives the value of life. It’s a matter of feeling, “I can’t take the way this is. It makes no sense to me.” There’s always feedback. It’s theory and practice. It doesn’t take some genius. It takes committed activists who are also willing to think and reflect. If you have activism but fail to go back and work out the context of the story, you lose. Sometimes academics are way off in some lofty sphere which has nothing to do with what’s going on in the ground. You have to be in both places at the same time.